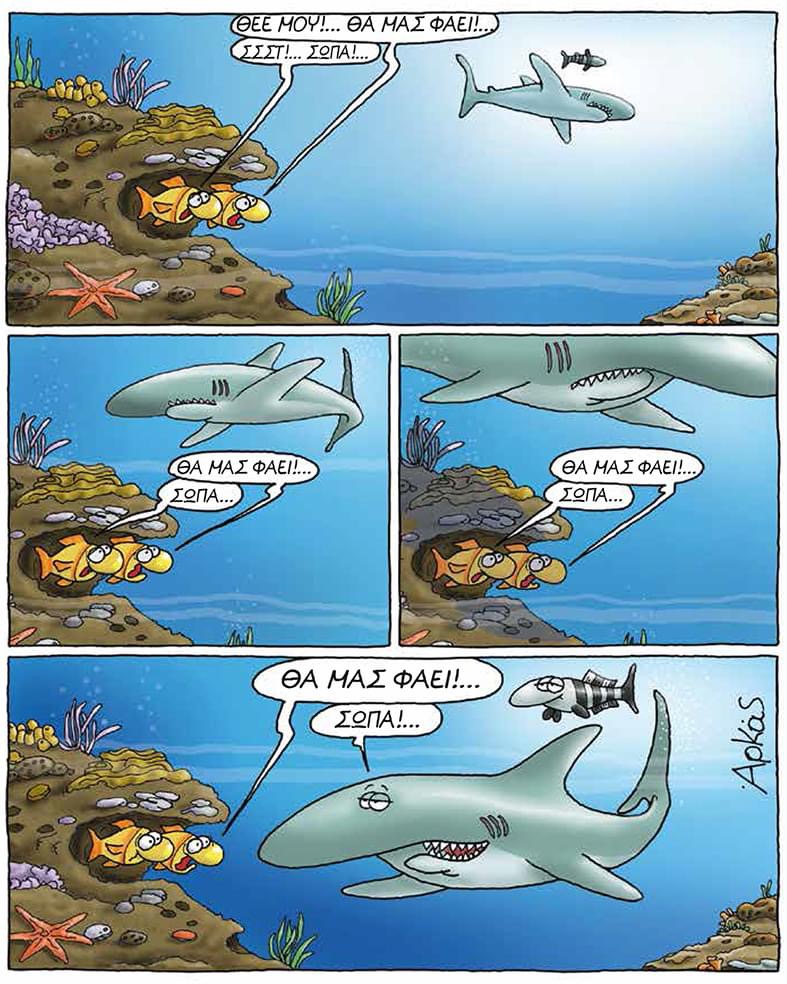

– Oh God!… It’ll eat us!…

– Shh!… Quiet!…

– It’ll eat us!…

– Quiet…

– It’ll eat us!…

– Quiet…

– It’ll eat us!…

– Oh, come on!…

I’ve already talked about polysemy on other occasions, but I’m returning to it because it’s a tricky subject in the translation world.

This comic strip provides a clear example of polysemy, that is, a word that can have multiple meanings. Almost always, there aren’t polysemous equivalents in other languages, so different words must be used. In doing so, the original idea of using the same word is lost, but at least the message content is conveyed.

In the example illustrated here, the Greek imperative σώπα is usually used to silence someone. However, sometimes it’s also used to respond ironically and can be translated as “oh, come on,” “yeah, right,” “no way,” and similar phrases. The shark in the comic strip is saying, “do you really think I’ll eat you?”; this is summed up in the brief remark, “oh, come on”.

Of course, as I mentioned before, one is forced to alter the original version because there isn’t a corresponding polysemy in English. However, translation helps to showcase the richness of the original language: in this case, it’s clear that in Greek there’s a single word that can be played with precisely because it can have different meanings.

In conclusion, not all setbacks are bad. The main purpose of translation is to convey the original message as faithfully as possible. Then, having to cancel polysemy in the translated version, if we have the original text for comparison, we can deduce the heterogeneity of the source language.